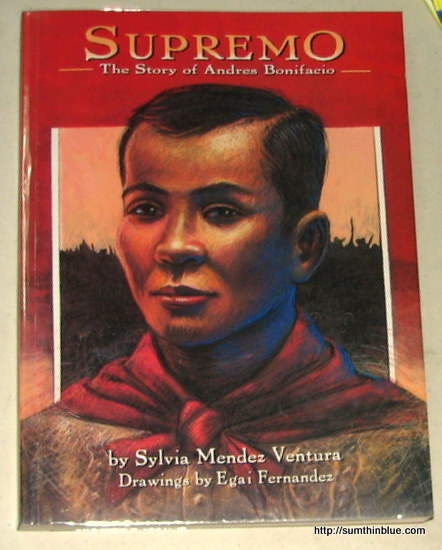

November 30 is Bonifacio Day, a day that commemorates the birth of Andres Bonifacio, Father of the Philippine Revolution. I’d been saving a book for this very occasion: Supremo by Sylvia Mendez Ventura, with drawings by Egai Fernandez, which I got at this year’s Manila International Book Fair.

While I’m predisposed towards being partial to Jose Rizal (I can’t help it — the educational system leans heavily on the national hero, but I also went to a school that counts Rizal among its alumni, and oh yes, I love Rizal’s geekiness), I’ve had a soft spot for Bonifacio when my high school Filipino teacher revealed he was a bookworm.

Supremo traces Bonifacio’s humble beginnings as the firstborn son of Santiago Bonifacio (a tailor and a town leader) and Catalina de Castro (head of a department in a cigarette factory) — neither ignorant nor dirt poor.

Bonifacio’s parents died before he could go to college, and he had to support his younger siblings — three brothers and two sisters. Despite not finishing formal education, Andres’ intelligence allowed him to get odd jobs around the city.

And my high school teacher was right: here’s a particularly interesting anecdote pertaining to Bonifacio’s bookishness, as recalled by one of his employers.

“Bonifacio worked as a warehouseman in a mosaic tile factory in Santa Mesa owned by the Preysler family. The lady proprietor, Dona Elvira Preysler, remembered Bonifacio as a bookworm and an inquisitive young man. He always had a book open in front of him even while he was eating lunch.”

And here’s more bookish trivia:

“As he grew to adulthood, Bonifacio steeped himself in books that opened his eyes to the dismal conditions of his time. Foremost of these were Rizal’s novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, which the government had banned as subversive. Bonifacio was also inspired by such books as Egene Sue’s The Wandering Jew, The Ruins of Palmyra: Meditations on the Revolution of the Empire (a widely read book about revolution as the solution to oppression and exploitation), the Holy Bible, Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, Lives of the Presidents of the United States, and novels by Alexander Dumas. He pored over books about the French Revolution, international law, the penal and civil codes, and even medicine.

Shutting a book, he would announce to Nonay [his younger sister] that he had just completed a course in law or in medicine. Once she asked him why he didn’t earn a degree for all the courses he was teaching himself. He replied, “I don’t want to earn a living by simply sitting down. I must earn by the sweat of my brow.” So well-versed was he in simple medical lore that he served as a sort of “barefoot doctor” in the neighborhood, ministering to the injured and sick whenever they needed him.”

The book, of course, goes on to narrate the birth of the Katipunan and Bonifacio’s leadership role in the organization; the Katipunan organ Kalayaan and Bonifacio’s own writings, an essay entitled “Ang Dapat Mabatid ng Mga Tagalog,” the poem “Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Bayan” (“Love of One’s Native Land”), the translation of Rizal’s poem “Mi Ultimo Adios” (My Last Farewell) and even the Decalogue of the Katipunan: “Mga Katungkulang Gagawin ng mga Anak ng Z. Ll. B.” or “Duties of the Sons of the People.”

And then the path to the remainder of Bonifacio’s short life is mapped out: Emilio Aguinaldo joins the Katipunan, Bonifacio consults Rizal on their plans to stage a revolution against the oppressive Spaniards (Rizal disapproved), the Katipunan is discovered by the Spanish government, and the revolution begins with an act of defiance: the Katipuneros tore their cedulas (certificate of taxes that proved one was a citizen in the colony) in an occasion that came to be known as “The Cry of Balintawak.”

As the revolution spread to the countryside, two factions formed in the Katipunan chapter in Cavite, one led by Bonifacio’s relative Mariano Alvarez, and the other led by Emilio Aguinldo. The bond that held the two factions weakened, and they eventually turned on one another, leading to the loss of faith in Bonifacio’s leadership, and ultimately the detriment of the Katipunan and its cause.

The saddest part comes in the final chapters — Bonifacio was tried by the Katipunan council of war and was, along with his two brothers pronounced guilty of “contriving to overthrow the the revolutionary government” and was violently executed in one of the mountains (Mount Nagpatong) in Maragondon. His death remains controversial to this day, because of various accounts of what had transpired. Bonifacio’s remains were eventually recovered, but were unfortunately lost when the National Museum was bombarded and burned in 1945.

I had thought this book would be a quick read, because I thought it was a book for younger readers. I was quite surprised when it turned out to be an extensive biography of Andres Bonifacio, because I had no idea there was enough information about him to fill over a hundred pages of text! The language is easy enough for a young reader to understand, but with the research that went into the book — the bibliography of reference books and articles for the book runs to to five whole pages, although understandably there are not very many primary sources (apparently “Bonifacio wrote little and lost most of his possessions in a fire.”) — it’s definitely a must-read for anyone who’s interested in Bonifacio.

I’m glad I read Supremo in celebration of Bonifacio Day — he truly is one of the greatest Filipinos of all time, and he deserves his place of honor in Philippine history.

***

Supremo, softcover, 4/5 stars

Book #168 of 2010

V for the A-Z Challenge

[amazonify]::omakase::300:250[/amazonify]

Thanks poh sa info!!!