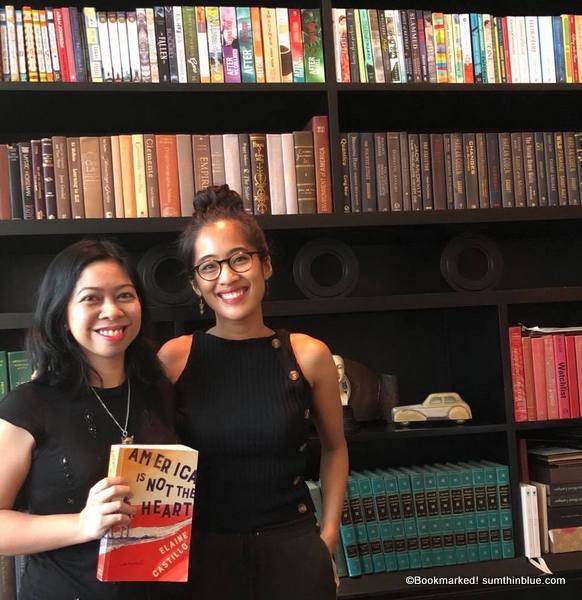

I’ve been taking introversion to new levels this year, the but I’m glad I made an exception this weekend, because I got to meet Elaine Castillo, author of “America Is Not The Heart,” who was in Manila for the Philippine International Lit Fest, right in time for the release of her acclaimed debut novel.

So I’m outside of my hidey-hole (and back on my blog, yay!), with a story for ABS-CBN News (here: http://news.abs-cbn.com/life/04/23/18/millennial-fil-am-writer-elaine-castillo-releases-debut-novel), and the interview in full below.

What inspired this book?

Before writing this novel, I’d been working on another novel, which I’d stopped working on for the good of all humanity. It was a terrible book. It was a book that came out of my youth at the time I was studying to be a classicist, and I think I was going to be the Filipino Anne Carson. I wanted to write my autobiography of a writer. It was a Greek myth-centered kind of book, about migration so I put it aside. In the summer of 2013, I wrote the prologue – those were the first words of that book that had been written, and that came out sort of intuitively, easily, in the way that writing sometimes happens (not always).

And for a long time I thought I was going to be writing a book about the 90’s Bay Area community that I came out of, but I started writing from Paz’s perspective and then started writing from Roni’s perspective. Originally I was going to write it from Roni’s perspective because autobiographically we share the most characteristics – we share the same town, our parents do most of the same things, but all the words were dead on the page. I had no idea how she sounded like and it was really super defensive writing, probably because I was too close to the facts of her life, and there was no oxygen in the room.

So at that point I had an idea in my head already for several years. I knew I wanted to write about a former NPA rebel who had been in exile… I knew I wanted to write about a loser. Hero (that wasn’t her name yet then) had already been in my head as a character, and so had Rosalyn and Jaime as exes in the Bay Area, and this is the point in a writer’s life when they think they have a lot of ideas but then they all turn out to be just one story. When I realized Hero was Roni’s cousin, and she entered the house in Milpitas, the world just sort of went up and I was able to sustain the writing for longer.

Until now, I still feel uncomfortable writing from Hero’s perspective. She comes from the kind of privilege I didn’t grow up with; I also didn’t want to write a protagonist that came from the kind of wealth that she did, but it was that discomfort and unease that gave me space to move, to write that if I wrote from Roni’s or Rosalyn’s or Paz’s perspective I wouldn’t have sustained for more of a chapter because I was so protective. So that’s how the book took its shape.

The scenes that happened in the Bay Area in the 90s, that’s a scene very familiar to me. The grain of it, the texture of it, I’m quite familiar. I did have to do a bit of research, I did most of the book living outside of the States, so you have to gut check yourself – is that street really there? Or did that song really come out in the 90s?

Both Martial Law and nursing were a big part of my family history, so some of it was taken from stories that I’ve heard. My parents weren’t hugely talkative about Martial Law, in the kind of way immigrants live in the post-traumatic silence. So a mixture of what I could eke out from what people would say and not say, and a bit of research also.

Did you study to become a writer?

No. In my undergrad I did comparative literature, but I was writing even when I was a kid. When I was a kid I had never said, “Oh I want to be a writer.” I would have said, “I want to become a singer,” because these were the fantasy things you think you’d become. Because [writing] was always the thing that I’d do and I didn’t realize that this thing I was doing all the time could actually be a career, not until high school. But I didn’t take creative writing in college. I turned to it late, when I was already 29, I took a writing MA in London.

How was the book picked up by your publisher?

Basically, it was because of the MA I was in, there was a kind of student reading. The woman who eventually became my agent happened to be there; I don’t think she was even looking for clients at that point. I think she was there for a friend. We sort of clicked and started talking, and she eventually became my agent. She read all the original pages written from Roni’s perspective and was just really an amazing sounding board in the gestation of the book, until we actually sold the book to a publisher.

What’s your writing process like?

A. I think it’s changed since writing this book, and also because I’ve gotten a bit older. I write in a mundane way. If I’m in the right frame of mind for writing, I wake up in the morning and sit down and write. If I have writer’s block, I tend not to write. Generally I do like to write in big chunks and edit as I go. Editing is always the fun part – it’s where you see everything you did wrong, and try to make it right.

Do you have a lot of people read your manuscript?

No, I don’t really have that many writing peers. I have friends who are writers, and we do talk about writing, but we don’t really show each other our work. I guess I’m not really workshoppy in that way. My agent, though, is one of my first readers. It means a lot to me that she’s a woman of color, especially if you’re working in a publishing industry in the US and the UK, which can feel very white. As a writer of color, you feel like the minute you give your manuscript away, all the eyes on it are typically white, and for me it’s meaningful to know that some of the early eyes on it are from a woman of color because obviously I’ve spent my life as a woman of color and my writing [stems from that].

How do you feel about the movement for diversity in literature?

It’s a long time in coming. Obviously we need more writers of color, characters of color. There’s a real dearth of diverse children’s literature – when I was growing up, I never saw a Filipino kid in the stories.

The other thing that’s equally important is there be structural change in the industry. What can often happen is that you diversify the front of the shop. You can diversify the titles and the characters, but the people making marketing decisions, sales decisions, are still ultimately the same type of people: typically white, typically middle class. I think that type of change is equally important.

As I said, it’s personally significant to me that my agent is a woman of color, as otherwise I would have attended many meetings as the only person of color. We need more agents of color, editors of color, publishing houses headed by people of color. We need diversity on all sides.

We’ve seen a lot of immigrant stories in Filipino American literature, why do you think it is important that these stories keep getting told?

Ultimately, it’s important because they’re American stories. If we want to have a reckoning with what the American reality looks like that’s worthy of being depicted in art, we have to have immigrant stories. It’s just a basic fact. I grew up in a minority town, mostly made up of immigrants: Filipino, Mexican, Vietnamese, Chinese, and for me it’s an American reality, but unfortunately that’s not a reality that I see being called the heart of America. And that’s outrageous, because otherwise, American fiction is a lie.

Food seems to be central to this novel – was that deliberate?

Absolutely not! I had no idea I wrote about food this much, until afterwards. People come up to me, and say, “There’s food on every page, I was starving reading this book!” If anything, to me, when I submitted this book, all I could think of was “I left this stuff out…” and I’m always like, “Oh, is it not normal to talk about food that much?” And then when I came here, suddenly everyone’s talking about food all the time, and I realized, it’s not just me, it’s a culture. Like last night, we were literally eating dinner, and yet we were still talking about food. I think this must be so saturated in my pores, like subconscious Filipino-ness, I had no idea that was not normal for everyone else.

The book has no italics, no glossary, no footnotes on Filipino expressions or cultural references, was this intentional?

I’m not writing ethnography. There’s plenty of books on middle class white life in Brooklyn – I don’t know what that’s like – and they don’t provide glossaries for me. I don’t really see why I should provide glossaries, and in doing so otherize my stake in American reality, which should be taken as such. On its own terms, unapologetic, not being made to be palatable to a particular audience which is assumed to be white, middle class and English speaking. It’s not to those eyes I am writing towards. So no [italics, glossaries], just jump in.

How do you feel about the reception the book is getting so far?

It’s completely surreal. When I can manage to think about it, consciously, and not just run away from everything, it’s just shattering. The kindness has been out of this world. I’ve had the luck of having really generous, incisive readers, and not every writer gets that, not every book that deserves it gets that, and I’m really grateful that there’s people who are willing to enter the world of the book and be receptive to the kind of space that it’s taking up.

Has your family read the book? Have they recognized themselves in the book?

They have not read it completely. Literacy is sort of a mixed bag in my family. But certainly there are some people who are like, “That’s your mom!” But not exactly. Because my mom knows that her life has provided a lot of textural details for the prologue, for a while she was like, ‘She’s written a book about me’ and (laughs) I don’t know how to break it to her that it’s actually about a bisexual communist. I don’t think anyone (in the family) has read it fully, but they’re all proud and excited about it. The entire diaspora is in my mom’s Facebook page.

How was your experience at PILF?

It’s just amazing. Honestly, truly, truly amazing. It’s that emoji with an arrow through the heart. This is only my third time in the Philippines. (NB: The next sentence is in white, slightly spoilery) My first time was when I was nine, and like in the story, I was kidnapped, which is why 22 years passed between my first visit and the next. Growing up, the only people I knew who could afford to go to the Philippines were upper middle class or middle class Filipinos, and I don’t think I’ve ever gone on vacation with my family, I don’t think my parents have ever gone on vacation. It wasn’t really a practical or material possibility for my life for all of my childhood. So to come here for the book, in a sense for the first time as an adult, to see Manila in my own terms – both my parents are probinsyano so we would go to provinces immediately after landing – is I think in a way life altering. It gave me something that I really didn’t have before, and I got to meet amazing writers, thinkers, artists. People were saying this particular event did a good job at representing different regions and I saw this really incredible panel about the literary scene in Socsargen. Just the depth and the breadth of critical discourse here, the creative practice here is so diverse that it puts the literary discourses I’ve stemmed from to shame. I really think I felt nourished in being here and I’m really just very very grateful to be here.

What’s on your reading list right now?

Everything I have bought from the festival. I can’t even close my suitcase. Immediately on my reading list are two new books by Kristin Ong Muslim that I bought. I’ve been a fan of hers for a while, I’ve read her work online, I love her speculative weird fiction genre writing. I got “The Drone Outside” and “Black Arcadia.” I want to read Glenn Diaz’s “The Quiet Ones,” he was on this panel with me and was so brilliant and incisive about migration and global capitalism. I got “Dead Balagtas,” which I’ve already started reading through it and it looks amazing.

Who are your literary influences?

Growing up I read a lot of writers in translation. When I was younger I had this unconscious aversion – though I don’t think when I was younger I would have politicized it that way” – to reading white American classic writers or even white English writers, which is why there’s huge gaps in my canon. I didn’t read George Eliot until I was an adult, things like that. Weirdly, I would get the books of anyone who looks foreign. Manuel Puig, this queer Argentinian writer who I love, who’s written “The Buenos Aires Affair,” and “Betrayed by Rita Hayworth.” Banana Yoshimoto, a Japanese writer who wrote “Kitchen,” that was quite formative for me when I was younger. Jamaica Kincaid, the Antiguan writer who wrote “Lucy” which was completely formative book for me, about female selfhood and identity in a way that was completely new to me. And then there’s Junot Diaz, I think there’s a whole generation of writers that are the kids of Junot, and I’m for sure one of them. A whole host of immigrant writers, writers in translation, writers in color. And of course there’s Anne Carson with the Greek myth on the side.

What’s next for you as a writer?

Definitely another novel, and maybe a book of essays. I like writing nonfiction and essays quite a lot. It’s good to have two spaces, so when I’m stuck on a novel I’ll go to the other.

What is your advice for Filipino writers?

First of all, write. Obviously read. That’s the advice that writers will always give you, read widely. But I would say, don’t make yourself palatable. If you’re a Filipino writer, or a writer of color within the larger mainstream American context, there’s that feeling of, ‘Oh do I have to deform myself to appeal to the mainstream public,’ and I would say reject that entirely. That is a poisonous idea, and it will poison your work. And ultimately that kind of idea says that the daily texture, the granular realities of your life and the lives you are drawing from are somehow not worthy of art, and I don’t think true. Don’t use italics, write in the vernacular. Stake the claim to your own particularness – writers have the right to that. There’s this idea that literature only sounds a certain way, and this is utter bullshit that needs to be pushed back against.

***

I have a recording of the talk at Writer’s Bar last Saturday (which I attended with my book club after my interview), but I don’t have time to transcribe the entire thing and some questions overlap with my interview anyway. I’ve transcribed a few more things worth noting, though.

On growing up Filipino American:

I was raised mainly with my mom’s family so Pangasinense and Tagalog were very much present in the house… I grew up in a majority minority community, with Filipinos, Mexicans, Vietnamese, so I never had a sense of myself as a minority, or had a sense of as ‘other’ in any way; the access to Filipino groceries and food was quite widespread and available, that was the particular context I was lucky enough to have grown in.

I know very well that I am a Filipino American, that’s a specific space that I occupy; I would never want to say that I’m Filipino in the way Filipino people born here are. I know that we have different contexts and formations, and I’m not trying to occupy that space. But to feel being Filipino, Pinay, I feel it very deeply.

On riffing on Carlos Bulosan’s ‘America is in the Heart’:

Being Filipina, I like a pun. Essentially, growing up, ‘America is in the Heart’ by Carlos Bulosan was the kind of foundational text for a Filipino American. It’s read in ethnic studies, it’s required reading in American history. It was meaningful for me — it was the first book I saw anyone from Pangasinan depicted. But whenever I saw the title, ‘America Is In The Heart,’ I would always have that little joke to myself that ‘America is NOT the heart,’ so eventually I went there, I knew I would write something with that title,” notes Castillo.

More on writing:

Don’t make yourself palatable. Don’t deform. Don’t write for some imaginary audience that is not like you. Don’t buy into this frankly fraudulent notion that literature is only for a certain strata of people, about a certain strata of people, or only exists in a certain language. That the literary is only written in English and everything else has to be in italics to telegraph its otherness. That is false. That perpetuates an idea of literature that ultimately means that everybody in this room isn’t allowed to be in literature. Own your space as a writer, and also write the work that only you can write because ultimately that is the work that readers like me or the kid that I was would have liked to read.

On Hero’s bisexuality:

She was always bi from the start. Of all my characters, there will always be a bi character because personally I am also bi. Bi visibility and bi ratio is important to me, and also depicting queer characters in their wholeness so that the depiction isn’t, “Here I am, I am the token queer person performing my queerness within the larger straight cast of characters. We have a queer woman who is undocumented, who is concerned about how she takes care of her cousin, is not just in a relationship with someone, but has to do things in a relationship, like how to be there for a new girlfriend. Those are the kind things I was interested in depicting, not just her as a queer character, but their love story — not just the beginning or the end, but the routine, the dailyness that goes into making a relationship work.

***

I finished reading the book in time for the interview (three quarters in one sitting!) and I have been recommending it to friends — I’ve read a lot of Filipino American literature in over nine years of book blogging (and even some in high school and college), but to me this is the book that has resonated the strongest. Maybe it’s because the writer is from my generation. But I think ultimately it’s because it doesn’t aspire to be anything more than what it truly is. Unburdened by an author belaboring to explain every single Filipino thing to a reader (who is probably more than 50% of the time Filipino), chronicle several centuries of personal and national history in one volume, or perform literary acrobatics just to show he/she can, this novel is a refreshing addition to the genre, and I find it more authentic and accessible at the same time.

(I have possibly a dozen friends reading the book now, so I won’t go into detail, but hit me up on messenger or wherever if you want to discuss!)

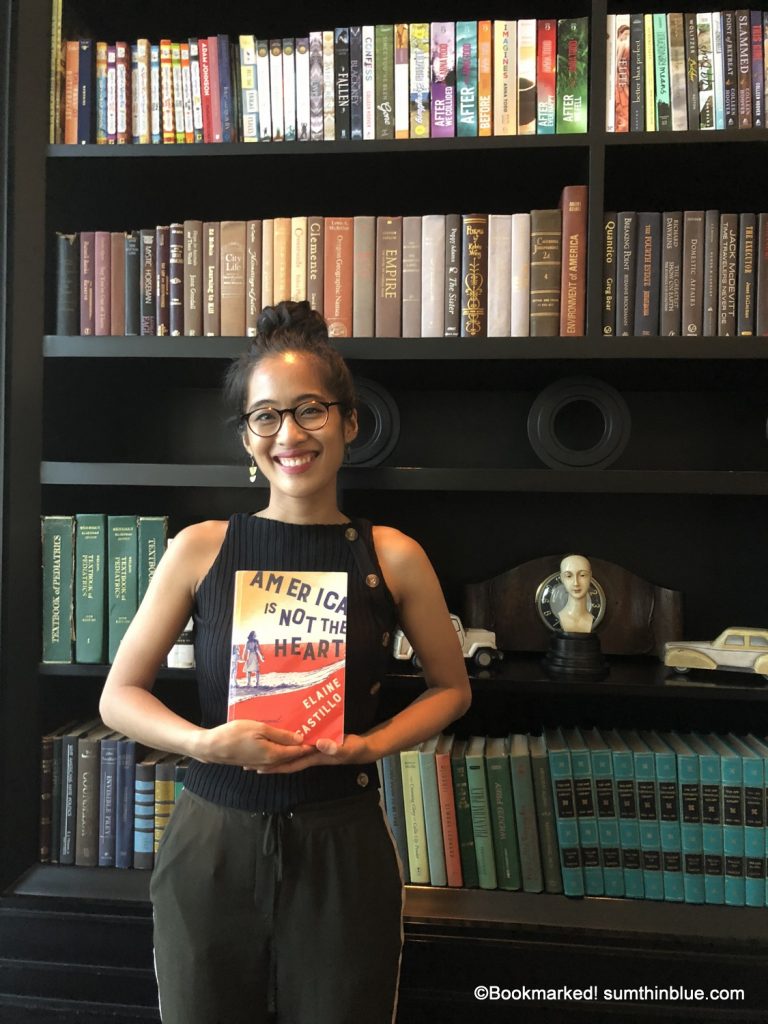

It was great chatting with Elaine, who was every bit as candid and as charming as her novel. I carved a stamp for her based on the book cover (she tells me the cover designer is of Filipino descent as well, slow clap), and she basically teared up when she saw it!

Of course I got my book stamped and signed!

***

Many thanks to friends at National Book Store (the book is available for P799) for arranging my interview, and Penguin Random House International for inviting FFP to the talk.

I have noticed you don’t monetize sumthinblue.com,

don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks

every month with new monetization method. This is the best

adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all sites), for more details simply search

in gooogle: murgrabia’s tools