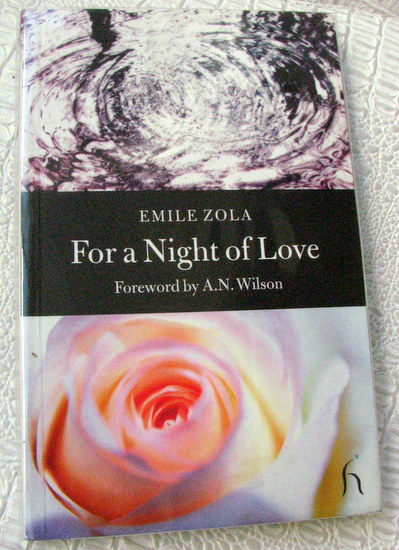

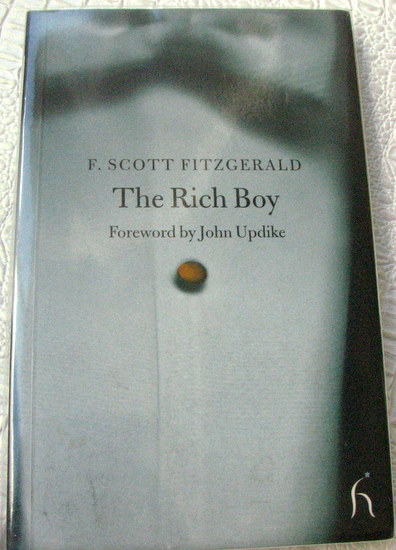

Since I joined the A-Z Challenge, I’ve crossed out three names on the list already. I first crossed off Trenton Lee Stewart with the first two books of the Mysterious Benedict Society, which I enjoyed tremendously. I managed to cross off two more: Emile Zola with For a Night of Love (Z); and F. Scott Fitzgerald with The Rich Boy (F).

The two books are published by Hesperus Press, a sophisticated imprint I’m growing fond of (I have Jonathan Swift’s Directions to Servants and a couple other books from Hesperus Press). Hesperus specializes in hard to find novellas and short stories of famous authors, with each book running to only 100 pages or so. I got a bunch of them on sale last year, and while I don’t normally like mass market paperbacks, Hesperus books are a welcome addition to my library — I love the concept behind the imprint and the elegance of the book design.

I got this whole bunch of Hesperus classics when one of my favorite book stores had them on sale, because I remembered a rule of thumb my Flipper friend Marie follows: if you’re trying out a writer for the first time, try their short story collections (or something to that effect…). I see her point — this way, you get a bite-sized piece that will give you a general idea of the writer’s style, and you can make up your mind on whether you want to quit early or move on to the writer’s, er, meatier works. These Hesperus classics fit the bill perfectly

For a Night of Love is a trio of stories by the most popular French novelist Emile Zola (in France, at least — Victor Hugo is more widely read in translation). This particular compilation is one 0f a kind; it is difficult to find a collection of Zola’s stories in English, as Zola’s novels are the more popular choice.

For a Night of Love is a trio of stories by the most popular French novelist Emile Zola (in France, at least — Victor Hugo is more widely read in translation). This particular compilation is one 0f a kind; it is difficult to find a collection of Zola’s stories in English, as Zola’s novels are the more popular choice.

The title story, the novella “For a Night of Love,” is inspired by Casanova, and tells of a plain-faced postal worker named Julien Michon, who is hopelessly in love with his next door neighbor, the beautiful but haughty Angelique. No matter what Julien does to profess his love and admiration for Angelique, she refuses to recognize his existence, until one night, when she gives him a proposition: if Julien disposes of her lover’s body, she will submit herself to him.

“Nantas” (pertaining to the title character) is about an impoverished yet ambitious young man struggling to make his fortune. The future seems bleak for Nantas, until his neighbor, the ravishing Flavie (who is pregnant), coaxes him into a shotgun wedding in exchange for a sizeable dowry.

Finally, there is “Fasting,” an anti-clerical tale about a noblewoman who derives earthly bliss from a sermon about ascetic self denial delivered by a decadent priest.

I’ve always wanted to read Zola, and I’m glad I started with this book. The stories capture what Zola is best known for — anti-Romantic naturalism, wherein history and the environment shape the protagonists and not the other way around. Zola likes throwing a varied set of characters into a catastrophic situation, and then sees how they cope with it. His writing is spare, intentionally veering away from the florid verbosity favored by Romanticism.

Meanwhile, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Rich Boy, the title story is quite controversial — it actually sparked a bit of conflict between Fitzgerald and his friend Ernest Hemingway when the latter took a line from The Rich Boy out of context. In the introduction by John Updike, he narrates that Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” contains the following passage:

Meanwhile, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Rich Boy, the title story is quite controversial — it actually sparked a bit of conflict between Fitzgerald and his friend Ernest Hemingway when the latter took a line from The Rich Boy out of context. In the introduction by John Updike, he narrates that Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” contains the following passage:

‘The rich were dull and they drank too much or they played too much backgammon. They were dull and they were repetitious. He remembered poor Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of them and how he had started a story once that began “The rich are different from you and me.” And how someone had said to Scott, Yes, they have more money. But that was not humorous to Scott. He thought they were a special glamorous race and when he found they weren’t it wrecked him just as much as any other thing that wrecked him.’

Fitzgerald was offended and wrote a response to Hemingway, a letter that was elegant, and yet succinctly conveyed his sentiments:

Dear Earnest,

Please lay off me in print. If I choose to write de profundis sometimes it doesn’t mean I want friends praying aloud over my corpse. No doubt you meant it kindly but it cost me a night’s sleep. And when you incorporate it (the story) in a book would you mind cutting my name?

Updike goes on to explain that Hemingway had taken the line out of context as Fitzgerald qualifies his initial statement with a rejoinder:

“They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand.”

Anyway, this whole tiff springs from the fact that the story is about a rich boy, Anson Hunter — born with a silver spoon in his mouth, the toast of the town in high-society Manhattan. Anson is everyone’s go-to guy, but there is a gaping hole in his life, left behind by a past love affair with Paula Legendre. The two other stories,” The Bridal Party” and ‘The Last of the Belles,” are written in the same vein, featuring the ill-fated upper crust couples Michael and Caroline, Andy and Ailie.

The protagonists are always the male characters, and they enshrine the women they love, with a conviction that they can never be truly happy unless they end up with these unattainable women. Of course, as Fitzgerald wrote these when his own marriage was falling apart, the stories debunk the myth of true love, and none of the protagonists end up with their ladyloves.

Fitzgerald’s stories are easy enough to read, but there is the pervasive atmosphere of failure and disillusionment, which number among the author’s perennial themes in his writings about the degeneration of the society during the Jazz age. While those themes are not my usual preference, of course I still want to read Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, The Great Gatsby (hmm, what’s a good edition of this book?), as well as his novella A Diamond as Big as the Ritz, which shares some common elements with one of my favorite books, The Twenty-One Balloons.

It’s a capital idea, reading snack-sized classics before taking in the feast. I think I’ll polish off the rest of my Hesperus Classics this year, and keep an eye out for a whole bunch more!

***

For a Night of Love, paperback, 5/5 stars

The Rich Boy, paperback, 4/5 stars

Books Z and F for the A-Z Challenge

Books 7 & 8 for 2010

[amazonify]::omakase::300:250[/amazonify]